This article is part of our Spotlight on Chinese American Authors. Sign up for our newsletter to receive family-friendly activity, recipe and craft ideas throughout the year!

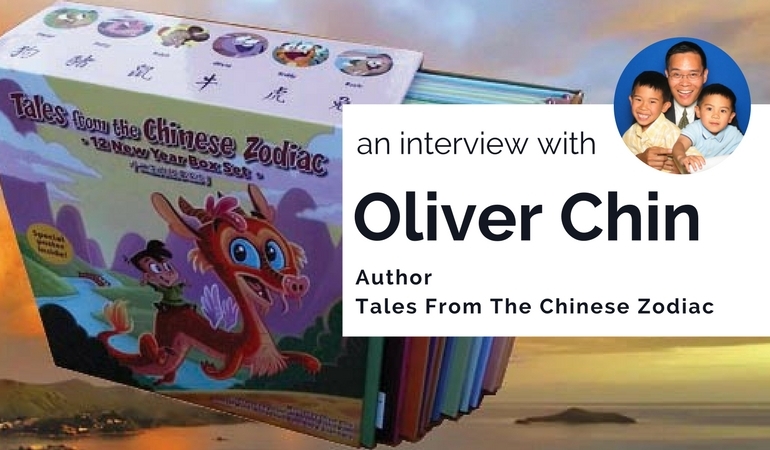

Oliver Chin is a busy man around Chinese New Year. The author of the Tales From The Chinese Zodiac children’s book series and the founder of the multicultural publishing house Immedium, Oliver is frequently on the road this time of year, presenting his books at schools, libraries and community centers around the country. A new edition of The Year of the Dog is his latest offering.

I recently spoke with Oliver with Chinese New Year approaching, a terrific opportunity during a season of renewal and fresh starts to talk about helping American kids find themselves in the stories of diverse cultures. Our conversation revealed how books can help kids and adults alike find commonality among diversity and build shared identities among people with different backgrounds.

Through the Tales From The Chinese Zodiac series, Oliver makes a simple proposition. That core qualities from traditional Chinese zodiac animals offer the foundation for new storytelling adventures that any child will find fun and can appreciate. Kids make personal connections that make new cultures less foreign and more accessible.

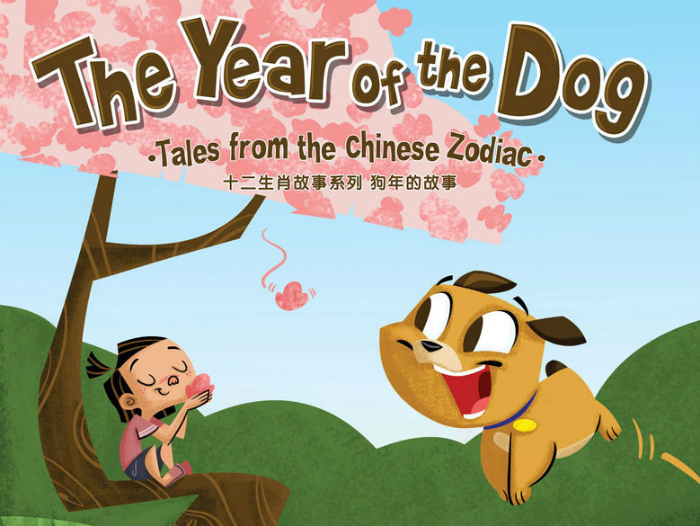

The Year of the Dog is an excellent example. Playfully illustrated by Miah Alcorn, The Year of the Dog follows a young pup named Daniel who befriends and protects a girl named Lin as they play in the neighborhood. During their travels, they encounter the other animals in the Chinese zodiac.

The storytelling in The Year of the Dog is light and fast-paced. The familiar zodiac qualities of a dog’s friendship and loyalty are present, but play a supporting role as Daniel follows his instincts and finds his own way in the world. It’s the difference between telling and showing how a person born in a particular year is believed to share the qualities of a given zodiac animal.

Oliver generously shared his perspective as an author and publisher. He talks about updating traditional stories for contemporary times, the magic of writing for children and a path toward greater appreciation of Chinese holidays in the United States. These are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Tell me about your childhood. How did you learn about the traditional Chinese New Year stories and zodiac tales that you now write about in your children’s books?

I’m a third generation Chinese American born in Los Angeles. When I was growing up, Chinatown was still centered downtown, so we would often go visit for the Chinese New Year parade or to go out to dinner with the whole family. My parents would always do the typical things like putting out oranges and tangerines on plates in every room, handing out lai see and telling us to clean up, but we wouldn’t necessarily do all the things you might read about in a book. After publishing all these books and presenting them at schools, museums and libraries each year, I actually attend many more Chinese New Year celebrations now than I did as a child!

My parents never told us Chinese New Year stories around a fireplace or as an evening tradition. We always knew what animals we were — my sister and my father were the only ones who shared the same one. For us, learning stories like the “Great Race” came much later. Publishing my series was a way to take traditional qualities and create brand new stories that have a modern, western point of view and appeal to any child here in America in the 21st century.

How do you celebrate Chinese New Year with your kids today? What’s new and what are your family traditions that you repeat each year?

My kids always know when Chinese New Year is coming because I get very busy and often I’m not around! Because my mother lives with us, they’re probably exposed to more Chinese culture, language and food than I was at their age. My mother in law will make a traditional dinner for us or we might go out. We don’t really blow it out like some other families do. It is a bit ironic that my celebrations at home are much more low key than the ones I attend as an author.

What role can children’s books like Tales from the Chinese Zodiac play in helping kids prepare for the holiday here in the United States?

There are many ways to educate kids about rituals, food and holidays — we try to go one step further. We’re not explicitly explaining something, but sharing an adventure where lessons can be learned through connotation or association, rather than through straightforward description. We enjoy telling fun and fantastical stories that may have a familiar starting point, but which won’t necessarily connect the dots to provide an answer or dictionary definition that you might expect. We want to appeal to a child’s imagination and offer adults something they will enjoy reading with their kids.

I’ve read recently about differences in the values found in Chinese and American children’s books. How do you approach writing to make your books appropriate for a Chinese American audience?

I do see how cultural commentators delineate the messages that come from one side of the Pacific versus the other and we don’t have a formula to split the difference. Having seen a lot of American entertainment growing up, most it was devoid of socially redeeming value, but we don’t necessarily want to push the meter all the way in the other direction. We start with the core qualities that make these animals special in the zodiac, which gives us anchors and landmarks to hit as we create an adventure in which characters chart their own paths and discover who they really are. It’s familiar to Americans because it’s a very dramatic Western concept of a hero’s journey, but rooting the story in personal qualities is something that a lot of Western TV shows don’t really care to do. It’s a means to make a more personal point, which hopefully becomes a universal one.

Parents buy the books initially because they want their children to know their year’s zodiac animal and what it represents, but kids learn they can pick any year and identify with the character’s travails and travels. They are stories any kid can identify with.

Chinese American families are increasingly diverse. What differences do you notice in Chinese American communities as you travel around the country?

Definitely language and culture. Clearly, in the past, most of the Chinese immigration to the United States was from southern China and Cantonese was the dominant dialect. If you go to any Chinatown, the conditions still reflect that. Within the last three decades, however, ethnic Chinese have been coming from everywhere, it doesn’t even have to be from China — places like Singapore, Vietnam and a number of other countries. We never claim to write for one particular group or another.

It’s actually more interesting to present to groups that are culturally diverse. As we expand our target, it’s gratifying to know that not only Asian Americans, but also others can appreciate the stories. The stories ring true because we’ve created characters that kids can see in themselves. They’re animals, but they have personalities and do impulsive things. Kids see these animals walk and talk and they can easily picture themselves in these stories.

You frequently present in front of mixed audiences. What broader interest in Chinese New Year do you see outside the Chinese American community?

More cities, institutions and commercial places are celebrating Chinese New Year. It’s spearheaded by Chinese Americans, but draws communities from all different backgrounds. It’s this dissemination of these celebrations that makes more people interested in participating. It’s easy to witness in San Francisco, Los Angeles or New York, but when smaller towns start celebrating the holiday on an annual basis, it becomes part of the fabric and people expect to participate in one way or another. That’s the way it should be, and it’s certainly more that way than it was when I was growing up.

Chinese New Year is a truly worldwide holiday, but it’s still not widely celebrated in schools or across American society. What’s the model for normalizing Chinese New Year for the entire country?

I wouldn’t say I have a model in mind, but can share my experience. For me, the holiday is a gateway to tell stories about the zodiac animals. The stories aren’t specific to Chinese New Year per se, but could be stories told as easily on Chinese New Year as on any other day. My approach to normalizing is to start a conversation that may seem unusual or foreign to someone who isn’t aware of it. Opening the door to understanding the cultural importance of the zodiac animals, and not just the ritual, makes the story something you can appreciate every day of the year.

It’s natural that a person would be most engaged with these stories on Chinese New Year, but when people see something as normal, they can say that it’s something they participate in. However, if it’s still draped in exoticism or a level of cultural otherness, that’s definitely still fine. People can still take pictures and be part of the crowd, but once it becomes personal to them, they can say something simple like, “Hey, I’m the year of the dog, what are you?” When you’re able to ingest it like that and it’s part of your personality, memory and identity, that’s the true goal of normalization.

###

Your turn! Have you read any of the Tales From The Chinese Zodiac series with your kids? What inspiration do you draw from Oliver’s experience?

Leave a Reply